[There has been an enormous amount of discussion on inflation, but most people do not understand the causes of inflation, let alone deflation. Because of this, I've copied the entire chapter on Inflation/Deflation from my book, “Forgive Us Our Debts,” into this web site for your easy reference. The book was written before the Pandemic, but recent updates appear in red.]

Once we have developed some financial humility, it is possible to open our minds to new approaches. To obtain that humility it was necessary to realize that most of our earlier and current sources of information about money, the economy, and investing came from questionable sources. That our belief system in these areas might not be true.

As we learned the real facts, we might have even felt cheated or angry. But that was the past. It serves no purpose to blame others or ourselves, but to simply choose again and start anew. This establishes hope. It is necessary, however, to make sure our new sources of information have no vested interest (investment) in how we accumulate and handle our money. Certain investment advisers seem to be the best choice. This was my approach starting many years ago, and it served me well. I carefully avoided those who were simply trying to justify sales of investments, and went out of my way to find the best minds in the world to learn the truth about money and investing. I will now share this with you.

Regardless of whether you have no money left over at month's end, or have accumulated a great deal of wealth, your opportunities are enormous over the next few years. This is because we are already starting to experience a period of extremely rapid and unprecedented economic change. If you enter this period knowing how money and the economy work, you have the opportunity to reach financial serenity. But the old ways of investing and managing money simply won't work.

Even if you "can't make ends meet," would you be interested in knowing there are ways to turn every $1 you can put your hands on today into $20-30 in a few years, after inflation? Do you think you just might be able to carve a few dollars out of your budget, or make a little extra money on the side to do this?

Such incredible gains might sound preposterous right now. You will soon decide otherwise. But it requires a new way of thinking. In fact, similar gains were made over recent decades. Let me explain. Our approach doesn't involve real estate, but assume you bought a house for $100,000 in 1970 with 10% down. Thirty years later it was worth $300,000, and you only had $10,000 of your own money in the property. If you sold at this price, and paid off the mortgage (you might have refinanced a couple times), you grew $1 of your own money into $30. Taxes must, of course, also be paid in this example, and mortgage payments were also made along the way. But this was possible because you made an appropriate investment, perhaps accidentally, during a period when it made sense to borrow heavily, leveraging your position. And inflation helped you do this.

Understanding debt and inflation is the key. But inflation has also created one of the greatest illusions of our time. Consider, for example, someone who bought and sold the exact same property as above, but was able to pay cash (no debt). The house increased in value from $100,000 to $300,000. Right? Wrong. The house did not appreciate in value at all! Because during that period the value, the purchasing power, of the dollar fell by almost three-fourths. Taking inflation into account, that $300,000 thirty years later would buy the exact same as $100,000 in 1970. But in this second example, the investment was actually a loser, because taxes on "illusionary gains" were paid. Inflation is perhaps the greatest hoax that could ever be pulled on a consuming public. It helped the

heavy debtor produce incredible real estate gains, but punished the cash-based buyer.

So our first basic step in learning about money and investing is to know exactly how inflation works, when to use debt, and how to prepare for the new period of something called deflation. Your basic training starts right now.

Inflation and Deflation Explained

It's first necessary to forget current definitions of inflation. I've even known a businessman who was one step away from becoming Vice-President of a huge multinational company, as well as economics majors, who didn't understand how inflation really works. In particular, totally forget the term disinflation. The term means nothing.

Let's start with a few simple definitions. They might be slightly different from what is found in some textbooks, but our objective is clarity and understanding for the average person, not a doctorate degree.

MONETARY INFLATION is a significant increase in the supply of money.

This might sound innocuous enough, but let's consider the ramifications. Assume all the wheat in the world this year sold for an average of $6 a bushel. If all the farmers in the world decided to plant nothing but wheat next year, and grew three times as much, what would you expect to happen to prices? If demand stayed about the same, and there was three times as much wheat, wouldn't you expect wheat to fall in value to about $2? This is exactly what happened to the dollar from 1975-1995 or from 1981-2021. There was a huge increase in the supply of money, and the dollar's value dropped by two-thirds, as measured by the Consumer Price Index.

PRICE INFLATION is an apparent general increase in prices, when caused by monetary inflation.

We measure prices in terms of dollars. And if the value of a dollar drops, prices appear to rise. If we treated wheat as a "currency" or barter tool, and priced everything in bushels of wheat this year, and in bushels of wheat next year (from our prior example), prices would seem to triple. This is exactly what happened over the two periods described, as prices measured in dollars appeared to triple. We're accustomed to using pints, feet, inches and other units of measure that don't change. But using something that constantly changes as a unit of measure is very deceiving. This reality and these two simple definitions will go far in correcting a faulty belief, and more importantly, prepare you to understand what has been occurring over the last several decades. Please think about this for a minute, to make sure you understand this important concept, before continuing.

MONETARY DEFLATION is a significant decrease in the supply of money.

This always occurs after long periods of inflation, as debts go bad, and describes the future. The results are exactly the opposite from inflation. When something becomes more rare, the value increases. In a deflation dollars disappear as investments plummet in value, or default. During deflationary periods the purchasing power of the dollar increases.

PRICE DEFLATION is an apparent general decrease in prices, when caused by monetary deflation.

Measuring prices in terms of something that is increasing in value makes it appear that prices are falling. But again, we're only seeing the effects of a changing unit of measurement. Remember that this not only affects what we buy. It influences anything denominated in dollars. Including investments and wages and salaries.

The only thing not directly affected is debt and its repayment. After incurring a monthly payment of only $300 on a house mortgage in 1970, repayment became dramatically easier as wages and salaries "increased" because of inflation over the years. But can you imagine how a monthly mortgage payment of $1200 would feel if deflation reduced your wages by three-fourths? And that would only take us from 1995 dollars back to 1970 dollar levels. Our current inflationary binge has been in place much longer than that. Any deflation completely removes all the debt created during the prior inflationary period. This deflation will return dollar value and "prices" to where they began in the 1960s. Deflation is a natural response to inflation, and the inflation/deflation cycle has been repeating itself for centuries.

Let me share one example about deflation. And never forget it. When inflation turns into deflation, massive changes occur in the price of certain investments. Most drop sharply in "price," but a few others rise dramatically. We will later describe which securities are involved, but assume you invested $1 today in those specific investments which rise in value. As the economy snaps and deflation (a negative Consumer Price Index) takes hold, your investment increases sharply in price. Your unique investment increases 60% a year for five years. This might sound preposterous. (Hint: The stock market crash on October 19, 1987, was an excellent one-day example of deflation. This particular investment increased in price from $40 to $6000 in that one single day.) At a more conservative 60% growth a year, in five years your $1 grows to $10 (or $6.50 in four years).

Let’s assume you can grow this type of investment ten-fold. But if deflation also increases the value of the dollar back to 1970 levels, each of those safe dollars will buy three to six times as much. So your initial $1 ends up with $30 - $60 in purchasing power. Deflation presents wonderful investment opportunities, if you understand the process and specifically choose the correct investments.

But you still don't know what causes the inflation/deflation process. We said that increases and decreases in the supply of money are the true cause of both price inflation and price deflation. Let's see exactly how that works. The supply of money today is most affected up and down because of the Reserve Banking System and borrowing. [And when the Fed creates money out of thin air.] There is one critical definition related to this discussion of banks:

THE MINIMUM RESERVE REQUIREMENT is the percentage of any deposit a bank must place in reserves (about 10%).

We now have all the definitions we need to describe how banks operate, and how the supply of money rises and falls. It's time to play bank, so you can personally experience how this process works.

Assume you and your family members own several banks. I come into your bank and deposit $100. Based on the above 10% Minimum Reserve Requirement, you must place $10 of my deposit in reserves. What do you do with the rest? You can either invest the remaining $90 or lend it to someone, to make money on that deposit and pay bills and shareholders. You decide to make it available for new loans. Mr. Creditworthy needs $90 to buy that new sports coat. You make the loan, perhaps via a credit card, and he buys the coat at Clothes R Us. At the end of the day, that business deposits the $90 in Dad's Bank. We now have $190 in total deposits. (My $100 plus $90 by the store.)

Wow! A new deposit. So dad sets aside $9 on reserve (10% of this second new deposit) and lends $81 to Mrs. Creditworthy. She uses the loan to buy jewelry at her local department store. The store deposits the $81 in Mom's Bank. We now have $271 in total deposits in our banking system.

Another new deposit… Mom puts 10% (about $8) on reserve, and lends $73 to Susie Spendthrift, who goes down and buys some new compact discs at Sound Heaven. At the end of the day, the record store deposits the $73 in your bank. We now have $344 in total bank deposits. I think you can see what's happening. That original $100 is working its way through the system, and deposits and the supply of money are growing like bunny rabbits. When we take this to completion we end up with $1000 in total deposits and $100 (10%) in reserves. The money supply has grown from $100 to $1000:

Deposits $100 90 81.00 72.90 .......$1000

Less 10% Reserve -10 -9 -8.10 -7.29 .….....-100

------ ----- ------- -------

New Loans $90 81 72.90 65.61 .........$900

This is how the money supply grows today - with borrowing via the banks. This is the true cause of inflation. The reverse occurs during a deflation. When a loan goes bad, banks must write off such amounts against their net worth and capital. This has the effect of reducing the amount of money for future lending. Less cash is available. During a period of loan defaults and a poor economy, prudence also dictates decreased lending. If not, such institutions can encounter regulatory problems. To raise cash a bank might even be forced to sell investments, such as stocks, bonds, or repossessed real estate. This has the effect of further reducing prices within these markets, and decreasing borrowers' collateral for subsequent loans. In sum, the money supply is equally leveraged in its ability to contract as well as expand.

[Instead of a $100 deposit, picture instead $5 trillion from the Fed, created out of thin air via their Assets/Balance Sheet like March, 2020 to March, 2022.]

One can determine how liquid, or brittle, the banking system is at any point, by determining what percentage banks are "loaned out." When financial institutions have lent more than 80% of all deposits, like today or in 1929, the system is extremely vulnerable to bad loans, and horrors, the possibility of a run on the bank. When the system is very liquid, and only 20-30% of deposits are loaned out like in the early 1940s following the last depression, such institutions are much more capable of dealing with fearful depositors.

This process also goes far in explaining why banks, savings and loans, and credit unions are experiencing such massive problems. Our typical "sources of information" tend to concentrate on bad management, fraud, and other types of explanations. You can now see the true underlying cause is a shaky financial structure, due to very low banking liquidity.

The above example did not cover "deposit insurance." Financial institutions also place a tiny percentage of deposits into an insurance corporation. Depositors are often content in knowing that deposits are insured. The Federal Savings & Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) is already bankrupt, and another insuring body has taken its place. The FDIC can only cover about 1% of total bank deposits with insurance. In fact, such insurance corporations were only designed to cover the one-off type of failures that periodically occur. They were never destined to bail out the entire banking system. And from the above, you can see the entire financial system is tightly entwined, especially when vulnerable due to low liquidity.

But, you say, the system is protected by the full faith and credit of the United States Government. As if they're in any better financial condition than the banking system itself! I certainly wouldn't pick the largest debtor country in the world, with its massive budget and trade deficits, to stand behind me. Remember one thing. Banks are businesses. They take in a product at wholesale (money deposits or loans from the Fed at low interest rates) and sell it at retail (loans at higher interest rates). Once the public demands that the government quit trying to bail out every major company in the country, to keep itself from going under, or our leaders in Washington reach their senses, it will finally be realized Uncle Sam couldn't possibly guarantee deposits to $100,000. And why should the average taxpayer (the majority) be expected to back the largest of depositors (the minority)? Fully expect this guarantee to be lowered to the $10,000 to $20,000 range, or eventually lower, as denial falls away, debts start going bad with increasing speed, and reality starts to prevail. [Major changes since 1996: One of the causes of the 1929 stock market crash, was during that time banks were allowed to speculate with depositors’ funds. So after the depression the Glass-Steagall Act was passed to prevent this from happening again. But much of it was reversed in 1999: The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) sought to end most regulations enacted by Glass-Steagall that prevented the merger of banks, stock brokerage companies, and insurance companies. This caused major problems during the financial crisis of 2008. How could the US Government bail out major banks when they were again full of speculative derivatives, when the FDIC was only meant to stand behind simple depositors’ funds? The barn door is again open, and trillions of derivative investments have been moved into retail deposit accounts. I believe that in 2008 the Fed was only able to keep things together temporarily, whereby if there were any potential runs on banks like in Greece or Cyprus, that the FDIC would be responsible not only for depositors’ funds, but trillions in derivatives. The next down phase will be exciting. This might require “bail-ins” for depositor monies, like in Greece, when you are severely restricted on what you can withdraw at any one time, regardless of how much you’ve deposited. This might also be described as a “war on cash.” When you deposit money in a checking or savings account, that money no longer belongs to you. Technically and legally, it becomes the property of the bank, and the bank just issues you what amounts to an IOU. As far as the bank is concerned, it’s an unsecured debt.]

The Fed Factor

The banking system plays a critical role in the entire process. But we haven't yet discussed another factor that has been extremely active in causing inflation. The Federal Reserve Board has used the banking system to try to control the economy. Picture a recessionary period. Businesses and individuals are complaining about bad business and high interest rates. It's time to crank up the banking system even further. Simply remember one thing. The Federal Reserve Bank also loans money to banks.

DISCOUNT RATE is the interest rate the Fed charges banks when they borrow money from the government.

If the Federal Reserve wants to move the economy out of recession, one thing they do is lower the Discount Rate. After all, if the banks can borrow money at a lower rate, they can charge lower interest rates to borrowers. Right? And if interest rates are lower, won't people borrow more, and therefore buy more, strengthening the economy? This is the objective…even if it leads to another higher wave of inflation.

Another critical action is the purchase, by the Federal Reserve Bank, of treasury bonds and treasury bills. When the Fed buys these securities from banks, this adds money to the banking system, just like our original $100 deposit. But this time we're talking about millions or billions of dollars, that might be only computer numbers, or "money" that never existed prior. As they pay dollars for the securities, this money enters the banking system. And the bunny rabbits start growing again, this time by the millions. [QE1, 2, and 3 saw the Fed buy $4.5 trillion in mostly debt securities, which has forced interest rates to artificially low levels. During the pandemic, the Fed 'printed' another $5 trillion. These numbers are shown in the Fed Balance Sheet.]

One other tool is for the Fed to actually lower the Minimum Reserve Requirement. Money supply can grow much more quickly if banks have to set aside less on reserve. This action is rarely taken, but when it does occur it causes massive changes in the value of investments. [This is a popular tool in China, however, and they've increased leverage twice in the last 5 years. Here's an even bigger shocker...see this link because our Minimum Reserve Requirement... is now ZERO!! ]

Of course the Fed can also take the opposite steps to slow down the economy or decrease inflation. 1980 was a perfect example of this. Inflation was clearly getting out of hand, voters were screaming, and it was time to do something. The first Fed action was to dramatically increase the Discount Rate. Banks were forced to greatly increase interest rates to borrowers. With extremely high interest rates, people borrowed less, therefore spent less, and the economy braked severely. As money supply dropped, inflation eventually came down hard. We experienced two recessions in four years.

The Fed also started selling government securities to fight inflation. (This is the opposite of when they bought securities from banks, which increased bank monies.) Money generated from those sales was taken out of the banking system, which made less money available for loans. This also had the effect of decreasing money supply.

Increasing the Minimum Reserve Requirement was not a step taken in 1980. But the overall effect was a sharp severe recession that broke the back of inflation during this 60-year inflation/deflation cycle.

The Powerless Federal Reserve Board

With such enormous power to influence interest rates, the money supply, and the economy, the Fed can prevent downturns in the economy. Right? Until 1986, yes…today, no. Here's the problem: In 1986 we became the world's largest debtor country. This important event changed the identity of our major creditors (government bondholders). We are no longer a closed system, depending only on domestic buyers of government bonds to finance our government's voracious needs for money. We now have to keep Japanese and particularly Chinese investors happy, so they keep buying our government bonds. How do you keep them happy? By offering interest rates high enough so they continue lending us money (buying our government bonds).

When the economy starts slowing, the Fed naturally decreases interest rates to increase borrowing from banks, move spending higher, and keep the money supply and the economy growing. But what effect would this have on foreign bond buyers? They would find our rates less attractive, and buy fewer bonds. If Washington is not careful, they can lower rates to spur the economy, but jeopardize their ability to borrow enough money to keep the federal government operating.

In fact, our economic future is now more dependent on what happens overseas than on what our Fed decides. This was illustrated in 1987 with the first leg of the coming stock market crash. To see what triggered that sharp crash, it's necessary you assume the role of a Japanese investor:

You had lent huge sums of money to the world's largest debtor country, by buying U.S. bonds. But you saw the value of your investment falling, because the dollar dropped against the Yen. To bring your money back to Japan, you need to sell bonds, and then buy Yen with those dollars. Fewer could be bought because the Yen currency exchange rate was rising against the dollar. You lost more than 10% on your investment for this reason alone. So you sold bond holdings or quit buying new bonds.

Market interest rates started rising because of less bond demand. To make bond interest rates more attractive, the Fed raised the Discount Rate. Higher interest rates are poison to heavily-indebted corporations, and future demand for their products and services became questionable. Everyone sold stocks, driving their price down 35% within two weeks (22% in only one day). Everyone had simply opened his eyes and seen that the American emperor had no clothes. The very next day, on October 20, 1987, it was later revealed that our financial system almost failed. That is how tenuous our financial system is. Now with the Japanese stock market already down more than 50% and still in serious trouble, the Nikkei alone could lead the way in the next worldwide deflation. [The Chinese stock market now plays the major critical role in the international financial community. The world financial system could become extremely volatile if their economy and/or stock market starts collapsing. Or China might decide to buy fewer of our treasury bonds, perhaps triggered by trade wars caused by sharply higher tariffs.]

Our spendthrift government has backed us into a corner. We no longer have control over our own monetary policy. But let's assume interest rates are lowered, without causing overseas lenders to boycott the purchase of our government's debt vehicles. Would there be an automatic increase in borrowing, the money supply, and inflation? No, not if one or a combination of the following occur:

- If banks can't or won't make sufficient loans to those wanting to borrow

- If people won't borrow because of a growing fear of debt or worries about job security

- If old loans are going bad or being repaid faster than new loans are being created

The first item has attracted much press. Regardless of their cost of money, if banks won’t borrow short term to lend long term, inflation cannot occur. Remember, debt is required for inflation to occur. Let's see how debt (or its absence) influences the "price" of investments. You want to sell a commercial property for $300,000. You find a buyer willing to put up $50,000 in cash, but needing to finance the rest. Depending on the economic period, let’s say banks won't make the loan. What is the real value of your property? Upon final analysis, it's only worth what someone will pay in cash. Before this deflation is over, this will occur with virtually everything. As prices fall, no bank will want to lend money to buy something that will soon fall below the value of the loan. Many companies have also gone back to the well and been refused additional credit. This alone is increasing the company bankruptcy rate. At the same time, more people are becoming ineligible for loans of any type.

The second item above is also occurring. Even if their credit rating is just fine, every day more people are "just saying no" to new debt. They are jumping off the debt treadmill that is strangling them. They're going cold turkey, finally recognizing their debt addiction. Some fear loss of jobs. Others will sell indebted assets, even at sharp discounts, before prices plunge even further.

Adjusting for Inflation

Because the purchasing power of the dollar changes so dramatically, it's necessary to adjust for fluctuations in any dollar transaction or investment. This includes the prices of goods or services in general. Only when we use constant dollars can we adjust for a changing unit of measure.

The first thing we need is a record of dollar value over time. The Consumer Price Index is the most popular index of dollar purchasing value:

(UPDATED) CONSUMER PRICE INDEX BY YEAR (December)

(Source: U.S. Department of Labor)

YEAR/CPI YEAR/CPI YEAR/CPI YEAR/CPI YEAR/CPI YEAR/CPI

1962 30.4 1973 46.2 1984 105.3 1995 153.5 2006 201.8 2017 246.5

1963 30.9 1974 51.9 1985 109.3 1996 158.6 2007 210.0 2018 251.2

1964 31.2 1975 55.5 1986 110.5 1997 161.3 2008 210.2 2019 257.0

1965 31.8 1976 58.2 1987 115.4 1998 163.9 2009 215.9 2020 260.5

1966 32.9 1977 62.1 1988 120.5 1999 168.3 2010 219.2 2021 278.8

1967 33.9 1978 67.7 1989 126.1 2000 174.0 2011 225.7

1968 34.5 1979 76.7 1990 133.8 2001 176.7 2012 229.6

1969 37.7 1980 86.3 1991 137.9 2002 180.9 2013 233.0

1970 39.8 1981 94.0 1992 141.9 2003 184.3 2014 234.8

1971 41.1 1982 97.6 1993 145.8 2004 190.3 2015 236.5

1972 42.5 1983 101.3 1994 149.7 2005 196.8 2016 241.4

The first thing we notice is a 2021 dollar is only worth 11% of a dollar (30.9/278.8) in 1963. In other words, 89% of the dollar's purchasing power was destroyed in the last 60 years.

We also need a simple formula to determine true price changes of anything, including investments. The following allows true calculation of the percentage increase, or decrease, of anything's value. True Percentage Return on Investment (% ROI) is:

(E - T) I1/I2

% ROI = ---------------- - 1 x 100

S

Rearranging, we get:

(I1)(E - T)

% ROI = ---------------- - 100

(I2)(S)(.01)

Where:

I1 = Inflation Index (CPI) at the time of original investment

I2 = Inflation Index (CPI) today, or when investment was sold

S = Starting investment (or original "price" of something)

E = Ending investment (or today's "price" of something)

T = Taxes paid

Example #1:

We bought a $10,000 one-year certificate of deposit in December, 1988, and it matured in December, 1989. So from the chart we see that the two CPI numbers are 120.5 and 126.1 There was a 7.5% interest rate on the CD. So our starting investment was $10,000 = S and our ending investment was this amount plus 7.5% interest ($750), for an ending investment of $10,750 = E. Assume a combined total state and federal tax rate of 25% on the $750 and we get $187.50 = T.

By plugging these numbers into the equation we get .93%. So after adjusting for taxes and the depreciating value of a dollar, we received less than 1% real return. Do such investments truly compensate for the risk of investing money in financial institutions that will soon again be failing at record rates?

Example #2:

We bought a stock in 1966 for $90, and sold it at $280 at the absolute highest price it reached in 1987 before the crash. (If we multiply by 10 we get the respective levels of the Dow Jones Industrial Average at those times.) Again assume a 25% total state and federal tax rate, and a 2% commission to buy and again to sell. Our original investment was $10,000 = S.

We received a 4.3% average (very typical) dividend every year, paid 25% taxes on dividends and placed the remainder into a money market fund that averaged 7% interest a year. Every year we paid taxes on that interest at 25%. After taxes, we had $16,507 in that account when we sold our stock. (This calculation is not shown.) We received $29,879 net from the stock sale. A 25% tax on the gain was $5,020 = T. We've already subtracted tax on dividends and money fund interest so the ending investment is $29,879 plus $16,507 = $46,386 = E. I1 was 32.5 in 1966, and I2 was 115.4 in 1987 from the chart.

If we hadn't paid taxes directly out of the money fund, we would appear to have a total of $30,010 in that fund plus $29,879 from the stock sale for a total of $59,889. That looks like a great deal for a $10,000 investment. But by plugging all the above numbers into the equation, we end up, after taxes and inflation, with a real percentage gain of 17.9%. That's less than 1% a year (.85%) real annual return. And that assumes we didn't suffer a massive decline in the 1987 crash. A $90 growth stock that didn't pay dividends would had to have increased in price to $413 just to break even. Of course this formula can also be used to measure the real percentage price change of anything from bread to new cars.

This is how illusions work. And inflation is perhaps the greatest illusion possible in investing and how we price things. These examples should hammer home the fact that prices seldom rise, but inflation is instead a loss in the value of a dollar.

Myths About Inflation

Many entities have been blamed for inflation: Big business, labor unions, higher oil prices, etc. Inflation is caused by the government itself, with the help of the banking system. Do you remember the WIN buttons under the Ford administration? WIN meant Whip Inflation Now. We were all asked to do our part to tame the inflation monster. Exactly how were we supposed to assist in this novel task? This was perhaps the most asinine suggestion ever proposed by the White House, even if it sounded good at the time and appeared patriotic. I'll leave you to ponder the motivation behind this action. Have you ever heard of a mushroom meeting? You put everyone in the dark, down in the basement, and feed them tons of bull____.

But wait a minute. Does this mean those "evil oil producers" weren't responsible for inflation when they jacked up oil prices in the 1970s? That's right. As they saw the value of the dollar plummet via inflation, they decided to catch up by increasing prices, and felt they were in a position to go even further. But this didn't affect U.S. inflation. This might not be obvious, so let's take a closer look.

The vast majority of households spend everything they earn, living paycheck to paycheck. If your monthly income is $3000 and you spend $3000 every month, perhaps $100 a month goes for oil-based products, particularly gasoline. If oil prices tripled, you'd be forced to spend $300 a month for such items. But suddenly you have $200 less to buy other things. So demand for other things must drop, and so would their price. OR you could borrow the money to continue buying the other things and...up goes the money supply. You push down on the waterbed here; it rises over there. If you don't spend everything you earn, you can buy fewer investments, real estate, etc., preventing asset inflation in the investment markets. It makes no difference. And how about "greedy businesses?" As a business owner, if you increased prices 50%, you would enrage your customers, and your competition would wipe you out. UNLESS you have no competition (are in a cartel, which was more true with OPEC during the 1970s). But there's only one way for prices in general to increase. That's when someone is messing with your money system.

It's rare, but even possible for inflation to occur when gold is used as money. In the 16th century Spain was hauling gold by the shipload from the New World to that country. This created a great European inflation, because the money supply increased.

Money can be inflated even when the total amount of gold or silver is constant. The government simply calls in all the precious metal coins, melts them down, and reissues a greater number of coins that contain greater amounts of other, cheaper metals. Has the U.S. government ever pulled such a trick? (Hint - silver coins after 1963.) Incidentally, what is the greatest inflation rate ever recorded in the United States? Inflation in 1974 and 1980 was a far cry from the record. As inflation surpassed 200%, we completely destroyed the Continental Dollar more than two centuries ago. And few people remember the Greenback from the 1800s.

I am also incensed by the government's implication they can "bring inflation back down to 0%." This first assumes they still have some degree of control, without destroying the economy, which earlier discussions sharply contradict. And since inflation is a function of money supply growth or contraction, debt increasing or decreasing, why should the growth of money have a floor at 0%? It either grows or contracts. There's nothing magical about 0%. Decades of inflation simply culminate in deflation (a negative inflation rate), as the debt pyramid crumbles. We then start all over again.

Summary

So there you have it. You now understand inflation and deflation. You also understand how debt is the key to both. It's also now obvious how tenuous our current financial situation is, and how little it can be manipulated as in the past.

If you don't understand the process, you are totally at the mercy of the system. If you understand and don't say anything, you can't complain. It's simply time to become actors instead of reactors. It's time to stop abdicating our lives to a government that will "fix things." Governments do not and cannot "fix" anything, at least in terms of economics and money. When you take a close look at government itself and how it operates, you will again come to one simple but true fact: Governments cannot create wealth. They can only influence its transfer from one group or individual to another.

Do you want to be on the receiving side, or remain in the dark in a mushroom meeting? By understanding money, how it works, and how it doesn't work, you've taken the first step towards financial sanity and serenity…regardless of your current situation.

This chapter was quite technical in nature, but true. Make sure you understand the major points before proceeding. Understanding how inflation and deflation work forms the basis for the much easier steps that follow. Go back and review this chapter, as many times as necessary, until you fully understand it. Discuss it with others who possess the same book or similar references until you're comfortable with the basics. Then continue without delay.

Click here to Review the Contents of the entire book

Click here to download a free PDF copy of "Forgive Us Our Debts"

***********************************************************************************************

The following IS NOT in the book, but graphics help describe how inflation works.

And suggests what the economy will do next. This will affect your investments.

First, try to avoid the term “higher prices.” In fact, the true measure of inflation is how much the dollar decreases in value, because of a higher money supply. In other words, the unit of measure is getting smaller, which looks like higher prices. For example, 60 years ago I paid 29¢ for a gallon of gas...3 silver dimes. Today the dollar is worth only 1/10th it's value back then. But those same 3 silver dimes, based on today's silver prices, are worth $5.60, and still buy a gallon.

As the money supply increases, each dollar becomes less valuable. There are 2 ways the money supply increases. The most common is banks make loans, creating debt. This increases the money supply. When debts are repaid, or defaulted, this decreases the money supply. Through reserve banking and loans, a bank can turn $1 deposit into $10. (See above book chapter for a precise example.) When the economy gets bad, the fed decreases interest rates to increase borrowing. When inflation gets bad, the fed increases interest rates to decrease borrowing. The second way for the money supply to increase is when the fed prints money, by creating brand new money that never before existed, which shows up on their Assets or Balance Sheet.

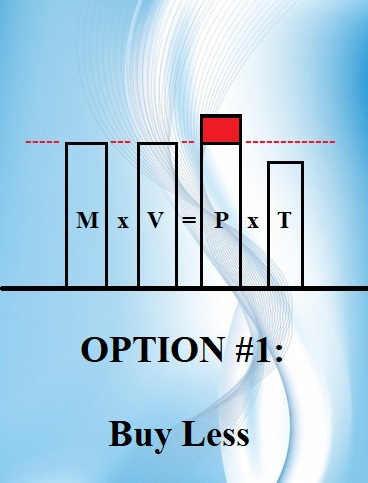

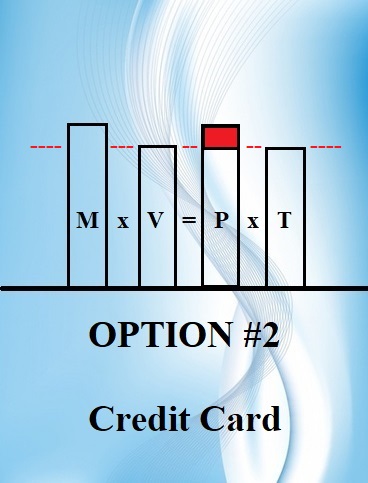

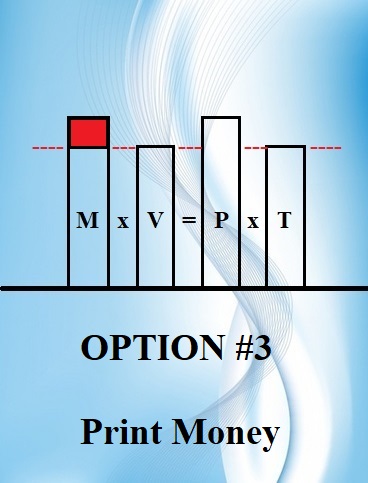

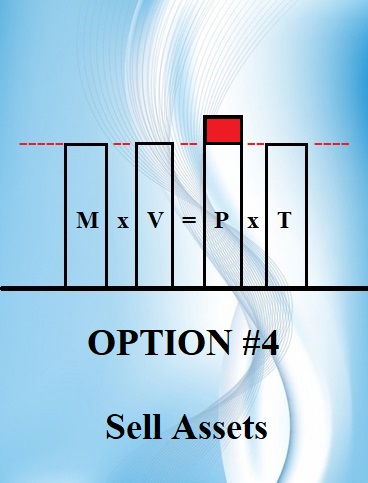

Here is the equation, which earned Milton Friedman the Nobel Prize in the 1970s. M is Money Supply, V is Velocity – How often each dollar moves through the economy every year. P is a Price Index, and T is the real Total Products/Services (inflation adjusted GDP).

Let's see how these numbers move around, using a family analogy. Assume M is your monthly income, $3000/month. Like 62% of Americans, you live paycheck to paycheck, and have nothing left after paying your bills. Assume a war disrupts oil supplies, increasing your expenses by $200/mo from higher gas prices, delivery costs, oil-based products, etc. If P goes up, what will the family do?

Option #1: If you spend less on other monthly purchases, less business if done, and T goes down to compensate. On a national basis, less total business can be called a recession.

Or you can use Option #2: You still buy the other stuff, by putting it on a credit card. Total business remains the same. But increased debt increases the money supply. Prices can go up first, but still affect an increase in debt. This is called cost push inflation. On a national basis, this causes M2, the money supply, to increase.

Or you can use Option #3: You can still buy the other stuff, because the Fed has printed $5 trillion of brand new money created out of thin air, and sent you stimulus checks. In fact, tens of millions of people have extra money to buy/bid up the price, of even more things. The government actually creates an inflation spike causing prices to rise. On a national basis, the pandemic was raging and economics threatened. This is the first time the Fed has printed this much new money, this fast, increasing M2 40% in 2 years.

Let's say you do have some investments on the side, and pick Option #4: You still buy the same products, but have to sell a little stock, bonds, or real estate to pay the extra costs. P has increased, but what goes down to compensate for it? The price of stocks, etc. would decline, which also tends to happen during recessions. On a national basis, CPI does not measure the rise or decline in the price/value of stocks, bonds, and real estate. Which is why “asset inflation” (or deflation) or “asset bubbles/crashes” are used to describe these “commodity prices.” CPI only includes monthly consumption expenses.

Actual: Here's what happened over the 2 years from 2020 to 2022 with this equation: The Fed manufactured $5 trillion out of thin air, influencing an unprecedented 40% increase in M2 Money supply! Because of the pandemic, Velocity of money passing through the economy collapsed 36% as business shriveled. The overall CPI increased P by 11% in those two years combined. Total business increased by 3%.

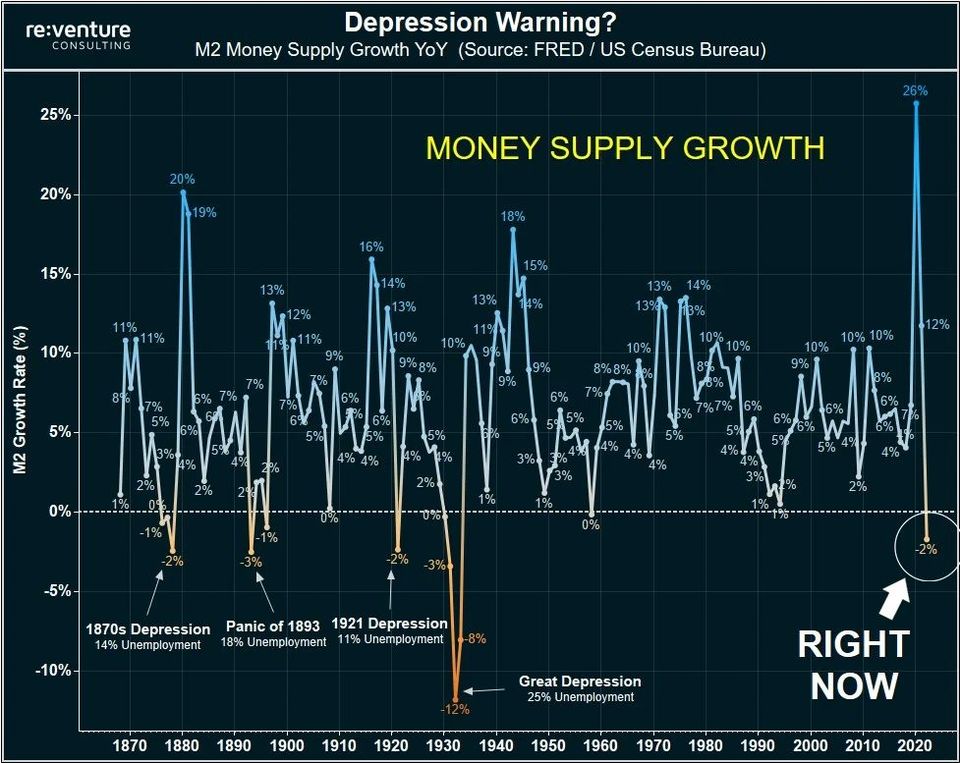

In conclusion, the money supply is what causes inflation. Either with cost-push inflation which creates more debt to pay for rising prices, or by the banks or the fed increasing money supply. But the fed is now sucking money out of the economy and increasing interest rates, to cure inflation. And the money supply is now decreasing. Fact (see graphic below): The last 4 times the money supply dropped, we had not a recession, but a depression and double-digit unemployment. M2 has now been dropping since Mar 2022. A repeat??

We hear of an expected “pivot” when the fed again starts lowering interest rates. Will this “save the economy?” No, another deflation/depression will occur if enough of the following occurs:

- If banks can't or won't make sufficient loans to those wanting borrow

- If people won't borrow because of a growing fear of debt or worries about job security

- If old loans are going bad or being repaid faster than new loans are being created